Previous Did You Know?

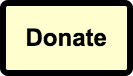

May 2023: Maine Lakes - Fact & Legend

Published almost a half-century ago, this 263-page tome contains an interesting assortment of information about Maine lakes.. In these pages, you will find no mention of Secchi readings, phosphorus or invasive plants. What you will find is a treasure trove of old photos, lake facts, history and trivia.

Although it has been out of print for years, the book’s publisher has now given us permission to post on this website a scanned version of the work. Check out the index to see which lakes are included or simply browse through this one-of-a-kind book!

February 2023: Maine Ice Data

Did you know that you can participate in collecting community science data? Lake Stewards of Maine tracks ice-in and ice-out on lakes throughout the state. This does not require special equipment or certification, just your time, thoughtfulness, and willingness to help! To get involved you can go to Lake Stewards of Maine’s Ice Data Page and read more about the program.

Sebago 5786 Photo by Claudia & Phil Lowe

Lake Stewards of Maine monitors, ice-in (the time when ice covers the lake surface), partial ice cover (a transitory stage on the lake, either ice has melted on a warm winter day or ice has developed on an especially cold autumn or spring day), and ice-out (when ice no longer covers ~90% of the lake, or is insubstantial). Click here to see the data collected this year. To see historical ice data please contact stewards@lakestewardsme.org.

Submit data here and thank you!

December 2022: Bird's Eye Views of Maine Lakes

Some time ago, we published a collection of some spectacular aerial videos of 26 Maine lakes, all captured by drones and published on YouTube or Facebook.

As our lakes begin to freeze this winter, take another look at these videos, all taken during the open-water months.

To view this collection, click on the image, below:

We welcome suggestions for similar videos from other lakes in Maine. To submit a video for this collection, please contact us.

September 2022: Invasive Aquatic Plants. Where are they?

As of early 2022, there were 7 species of invasive aquatic plants in Maine - in a total of 32 waterbodies (or groups of closely associated waterbodies). The most common taxon is Variable leaf milfoil (in 25 waterbodies). The other species are: Eurasian water milfoil, Curly leaf pondweed, Brittle naiad (also known as Brittle waternymph), European frogbit, Parrot feather, and Hydrilla. Most of the occurrences are south of Bangor, the notable exception being Big Lake & Lewy Lake in Downeast Maine.

Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has produced a map showing the distribution of these species. An interactive map is here. Read more about Maine’s aquatic invaders on the pages of these organizations (among others): DEP, Lake Stewards of Maine (LSM), and Lakes Environmental Association (LEA).

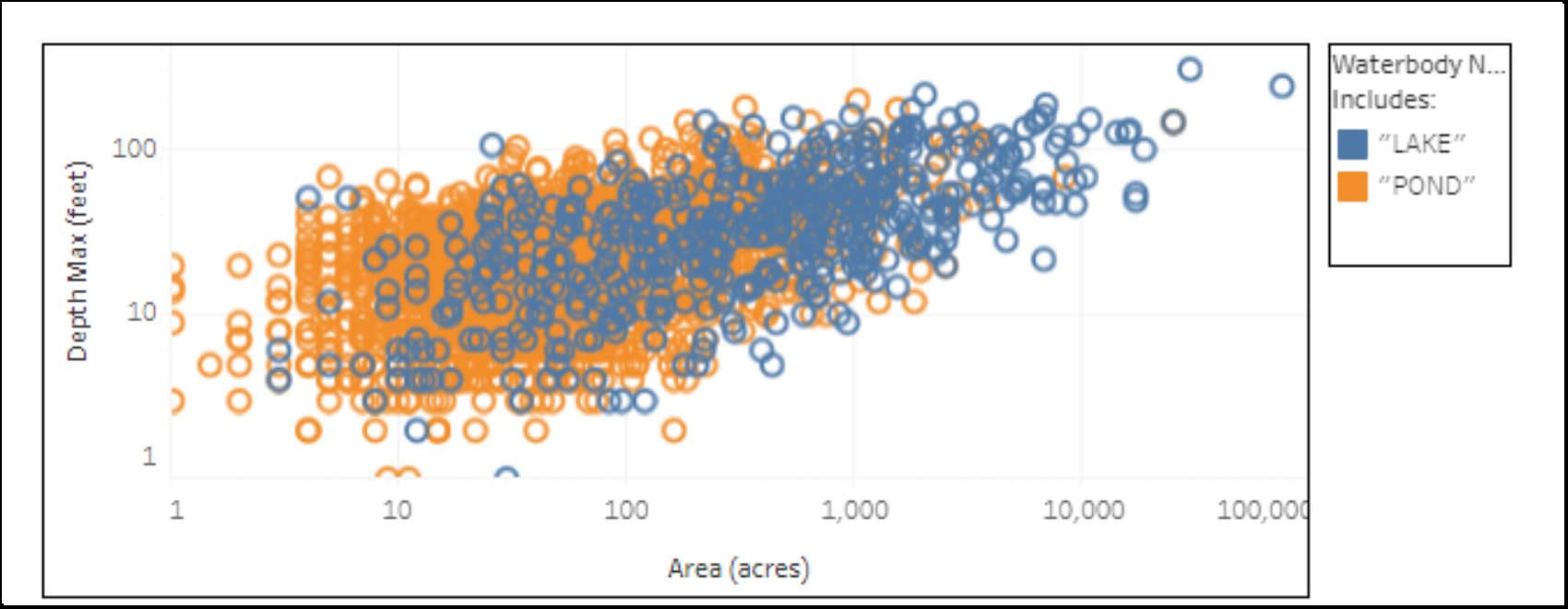

June 2022: Is it a Lake? Is it a Pond?

People often ask: is the difference between a lake and a pond? Back in 2010, Linda Bacon (ME DEP) wrote an informative article in VLMP’s Water Column newsletter *. Quoting Linda, “One classic distinction is that sunlight penetrates to the bottom of all areas of a pond in contrast to lakes, which have deep waters that receive no sunlight at all. Another is that ponds generally have small surface areas and lakes have large surfaces…..Some of Maine’s large and deep bodies of water are indisputably lakes. Others are ponds – small and shallow. But there is a transition between the two where the definition becomes fuzzy…..The one distinction that has any legal application is the designation of a body of water as a Great Pond. Maine state statutes define lakes and ponds greater than ten acres in size as Great Ponds…..” Read more about the differences between lakes and ponds HERE.

A waterbody’s name, however, is certainly not a clear guide as to its biological / limnological status - as illustrated by these two waterbodies, both on Mount Desert Island. Some so-called Ponds are clearly lakes. Some so-called Lakes function more like ponds.

To delve further into how waterbody names (“lake” / “pond”) relate (or don’t) to size, take a look at this interactive graphic

* Bacon, L. 2010. Lake or Pond???. The Water Column Vol 15, No. 2

March 2022: Adirondack Lakes

How watershed vegetation & atmospheric deposition influence lake water quality

Drive approximately 270 miles west from Bethel, Maine, and you will come to the Adirondack Park, 6.1 million acres that contain more than 10,000 lakes, 30,000 miles of rivers and streams, and an estimated 200,000 acres of old-growth forest. In an excellent video about Adirondack lake science, researchers describe how they have been sampling hundreds of lakes in the Park using a custom-built twin-prop float plane. They also explain how wetlands, upland vegetation communities and atmospheric pollution (nitrogen, especially) influence lake water chemistry.

This well-produced video is a great introduction to some facets of lake science - ecosystem processes that are as relevant to Maine lakes as they are to the lakes of upstate New York.

August 2021: LSM / VLMP Celebrates 50 Years!

A half-century that has seen thousands of volunteers collecting data from over 1000 Maine lakes!

Over the past 5 decades, volunteers & others throughout Maine have produced an incredibly rich lakes data set - including more than 138,000 Secchi disk measurements, over 44,000 temperature-dissolved oxygen profiles, and many other measurements on lake chemistry & biology.

Listen to 3 lake scientists, each with several decades of experience working with Maine lakes, as they share their thoughts on the conservation & management of our lakes, the role of LSM, and the many dedicated citizen scientists who have contributed so much to an understanding of these ecosystems.

These video clips are from LSM’s annual conference, July 2021. Click on names to access the videos.

Matt Scott (click for video) is an aquatic biologist, a founder of ME DEP’s Lakes Program as well as of VLMP, former deputy commissioner of IF&W and Master Maine Guide. Matt shares his insights on the origins of VLMP and his recollections of many of the people involved with the lakes of our state over the years.

Dave Courtemanch (click for video) is a freshwater scientist at The Nature Conservancy and is a former director of DEP’s Division of Environmental Assessment. Dave underscores the value of long-term data - a resource made possible by LSM/VLMP volunteers monitoring Maine lakes.

Steve Norton (click for video) is Professor Emeritus in the School of Earth & Climate Sciences, University of Maine. Steve pays tribute to LSM/VLMP volunteers and explains some of the ways in which the lakes database is being used to help manage and protect this part of our natural heritage.

Also, Scott Williams (LSM Executive Director) has produced a short article about the early years of VLMP and the treasure trove of Secchi data produced by volunteers.

April 2021: A Pioneer Lake Ecologist

To many aquatic ecologists (and indeed policy-makers) this is one of the most iconic lake photos. It is of Lake 226 in the Experimental Lakes Area (ELA) of northwestern Ontario, Canada. It shows a whole-lake experiment demonstrating the influence of phosphorus on water quality. To set the stage, it was the early 1970s; there was a debate raging about the causes of noxious algal blooms and their many effects on lake ecosystems. Detergents and fertilizers were major sources of phosphorus. However, rather than phosphates, the soap industry at the time lay the blame for algal blooms on carbon and nitrogen. While laboratory experiments could readily demonstrate the influence of phosphorus, a larger-scale demonstration was needed to drive home the point to regulatory agencies. So ELA scientists placed a rubber curtain across Lake 226. To one side, they added carbon and nitrogen. To the other, they added phosphates as well as carbon and nitrogen. Within weeks, the phosphate side “exploded into teeming green soup.”

The lead scientist in this study - and much other research on boreal ecosystems - was Minnesotan native David Schindler. Schindler died last month. Read this tribute to find out much more about someone who is considered to be “among the most important and effective ecologists and environmental scientists in history...”

David Schindler (1940-2021)

March 2021: Ice Safety and Thickness

The late onset of solid ice in Maine was a source of frustration for some. It highlights the serious issue of climate disruption, caused in-part by global warming. Now that cold weather has come to Maine people are out on the ice with increasing regularity. Maine Inland Fisheries and Wildlife offers helpful information about ice thickness and safety on their website. Here are a few helpful tips:

- An average person needs a minimum of approximately 5.1 cm (2”) of solid ice to safely walk on the surface of a “clear, blue lake”.

- A river requires an even greater thickness due to the moving water.

- Not all waterbodies are the same. Both shallow ponds and lakes that are darkly colored -- due to the presence of natural tannins and other organic compounds -- tend to absorb more energy from the sun making their ice less stable.

- Ice thickness can vary across a lake or river; it is important to be cautious even after testing the ice in one spot.

- Upwelling of warm water can cause weak points in a lake or stream. These can be caused by multiple factors including groundwater seeps.

- Ice depth in areas close to tributaries (incoming water) is likely to be thinner and more variable, depending on the size of the stream and flow.

- Strong winds can weaken or even break up areas that have iced over by mixing water in the lake.

- A parked vehicle or other heavy object with little surface area in contact with the lake can melt the ice beneath it, causing the object to slowly sink into the ice and potentially weaken the ice in that area.

- Multiple people all walking together (but in single file) requires a greater thickness of ice for safe passage, approximately 7.7 cm (3”).

- The 2020 & ‘21 winter season started off much warmer than usual, so although we have had recent cold temperatures, it is likely that waterbodies are warmer and ice is thinner overall, than some other years. This means that ice will likely become weak earlier in the spring of 2021 and people should be more cautious as the season advances.

October 2020: The Cooper Lake Surveys

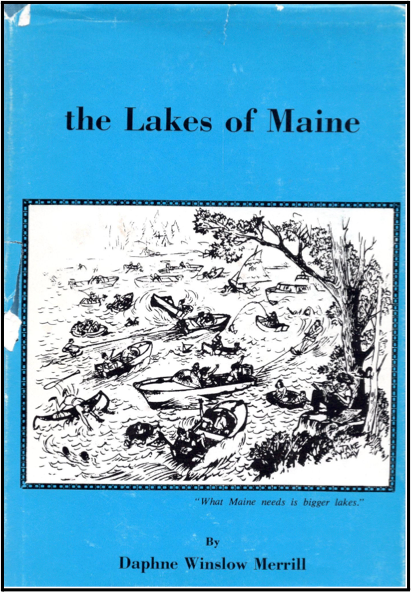

The year is 1937. Across the Atlantic, the Spanish civil war is raging. Somewhere over the Pacific, Amelia Earhart is last heard from. In the US, FDR opens the Golden Gate Bridge; the Hindenburg airship is destroyed at Lakehurst NJ; Spam is first sold in food stores. And, in Maine, Gerald Cooper, a faculty member at UMaine, begins the first systematic survey of the water quality and biology of Maine lakes (and some streams). During this first year, Cooper focuses on streams and a few lakes in York and Cumberland counties. Over the next 7 years (with a break during the war year of 1943), Cooper and colleagues survey over 200 lakes, ending up with Moosehead and Haymock Lakes in 1944.

A key reason for the Cooper surveys was to evaluate lakes for fish-stocking. They collected data on: lake depth, water temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, phosphorus, benthic invertebrates, and plankton & fish communities. Cooper did not measure water transparency. Therefore (and unfortunately, given the ever-expanding base of Secchi data collected by LSM volunteers and others) it is not possible to explore how transparency in these lakes has changed over the 8 decades since these historical surveys were carried out.

The results of the surveys were published in a series of seven Fish Survey Reports. An interactive map showing where the lake surveys happened is HERE.

Cooper et al. used gill and seine nets to collect fish. Supplemented by information from fish & game wardens, they thus documented the structure of the fish community in each surveyed lake (species composition, diets, age/growth). By comparing these data with more contemporary data from IF&W, it is possible to examine changes in lake fish communities over the past ~ 60 years. Especially interesting is the ‘spread’ of such species as largemouth and smallmouth bass as a result of both intentional and illegal stocking (and ‘natural’ range expansion).

Explore these changes in Maine’s lake fish communities HERE.

September 2020: Maine's Oldest Lake

It's the end of the last ice-age. The glacier that covers northeastern North America with a 1.5-mile thick layer of ice starts to melt. Its edge is near Georges Bank in the Gulf of Maine. Around 16,000 years ago, the first rocky island emerges from the ice sheet to form what will one day become mountain tops in today's Acadia National Park. Meltwater fills a basin in the granite rock to form Maine's first lake - Sargent Mountain Pond.

Catherine Schmitt has written about Sargent Mountain Pond:

“...Three thousand years later, to the north, Katahdin emerges from beneath the ice and snow; to the south, woolly mammoths browse on shrubby willows, ferns, and sedges taking root on the newly exposed tundra. Nomadic people follow the path of the receding ice to hunt and fish…..Centuries pass. The [ocean] shoreline drops as the land, freed from the weight of the ice, slowly rebounds to its now-familiar position. Salmon are stranded in Sebec, Sebago, Green, and West Grand lakes. Mammoths retreat and whales head for deeper waters.”

Around 12,000 years ago, forest vegetation first develops around Sargent Mountain Pond.

Catherine's full story is HERE.

Several years ago, Steve Norton, Steve Kahl, Randall Perry and other scientists from the University of Maine drilled down through the winter ice to take cores of the lake's sediments. Using chemical and biological analyses of these cores, they have described many aspects of the history of Sargent Mountain Pond. Perry's research is HERE. Find other research articles on this lake using Google Scholar.

Sargent Mountain Pond is on what must be one of the most visually stunning hiking trails in Maine. Joe Braun has an excellent photographic tour of the trail that includes this lake.

June 2020: Black Bass

Black bass are favorite targets for many anglers. Although they have been in Maine since the 1800s, largemouth and smallmouth bass are not native to our state. The first recorded largemouth introduction was in Forbes Pond in Gouldsboro in 1897. Today, there are more smallmouth lakes in Maine than largemouth lakes. Use our Species Mapper to explore the distributions of these 2 black bass species in Maine lakes.

Although illegal introductions continue, the ME Dept. of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife no longer stocks largemouth or smallmouth bass. The only species currently stocked by IF&W are salmonids — brook, lake, brown and rainbow trout, landlocked salmon and splake. You can find out which lakes and rivers were stocked in 2020 HERE. More on bass management in Maine is HERE.

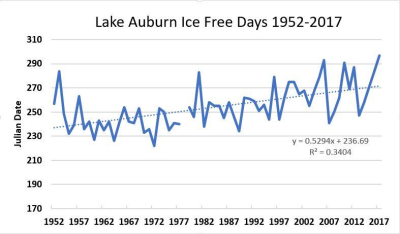

February 2020: Ice-out Dates

Records of ice-out dates for 18 Maine lakes extend back into the 1800s, with the longest data set being from Sebago lake (first ice-out record: 1807). In the case of Auburn Lake, ice-out records begin in 1836. In the recent LSM newsletter, Lloyd Irland writes about “Maine Lake Ice-Out Dates and Ice-Free Periods: What’s the Trend?” For Auburn Lake, Irland shows that there has been a “striking increase of 26 ice-free days between the averages of 1952-1971, and the 1998-2017“ (see figure, below). Discover more about ice-out trends for Maine lakes HERE.

November 2019: Water Transparency & an Italian Priest

There are over 140,000 Secchi readings from Maine lakes on this website — most of them collected by volunteers. The circular disk, familiar to all lake citizen scientists, was invented in 1865 by an Italian Jesuit priest, Pietro Angelo Secchi. He had been invited to join a research cruise on a ship (the “Immacolata Concezione”) of the Pontifical Navy to find an objective method to measure water clarity. Secchi’s original white disk was modified in 1899 by an American civil engineer, George Whipple, to the black and white version we now use.

Angelo Secchi was an extremely accomplished scientist. While his main field of scientific interest was astronomical spectroscopy, he also studied meteorology and oceanography. For a while, he taught at Georgetown University before returning to Rome in 1850. Over his career, he published over 700 scientific works.

For more information on Angelo Secchi, here is one source.

To access the various data sets containing Secchi data, click HERE.

September 2019: What you can find on LakesofMaine.org

On lakesofmaine.org you can find:

- Water quality from all 1,065 surveyed lakes in Maine

- Lists of fish species present in 2,342 lakes and aquatic plants in more than 410 lakes

- Interactive species distribution maps for fish, plants, crayfish and mussels

- Loon census data

- Maps of conservation lands around your lake

- Boat launches